By MOSES OGUTU

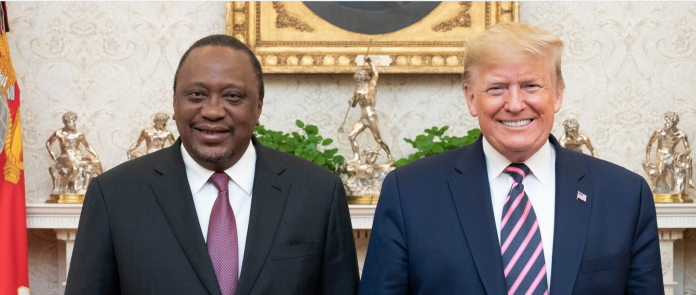

In February 2020, US President Donald Trump and Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta announced their intention to pursue a free trade agreement (FTA). By March, President Trump had formally notified Congress of its intention to commence the negotiations of what would be the US’ second FTA (the first being with Morocco in 2004) and by 27 May a summary of the negotiating objectives had been released. In pursuing the negotiations, the US noted it would “seek a mutually beneficial trade agreement that can serve as a model for additional agreements across Africa” and “build on the objectives of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), promote good governance and the rule of law.”

The goal is therefore to reach an agreement that builds on the objectives of the AGOA and that will establish a foundation for expanding US–Africa trade and investment. But Kenya’s unilateral decision to pursue an FTA with the US has triggered critiques from members of the East African Community (EAC) and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Both the EAC and the AfCFTA agreements discourage members from pursuing bilateral trade deals with third parties. Though Kenya has downplayed these concerns, the outcome of the negotiations will nevertheless have significant consequences for intra-African trade, as well as Kenya’s influence across the continent.

US motivations: Maintaining influence in Africa

Kenya’s geo-strategic location in East Africa sits at the intersection of US, Chinese, and other Western interests. For the US, Kenya is an economic powerhouse in Eastern Africa that is vital to the entry of US companies in the region as well as for the US’ war on terror in the Horn of Africa, in particular its counterterrorism efforts against Al Shabaab in Somalia. However, China is also aware of Kenya’s value, as it sees the country as an entry point for Chinese investment into the rest of the continent and has even pursued an FTA with the EAC to this end, but ultimately failed.

“The proposed FTA is a largely symbolic manoeuvre by the US geared at neutralising China’s influence in Africa.”

Indicative of growing relations between the US and Kenya, in 2018, Kenya was invited to join the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS and during the anniversary of 55 years of bilateral relations in 2018, President Trump and President Kenyatta “resolved to elevate the relationship to a Strategic Partnership”. A US–Kenya Trade and Investment Working Group was subsequently established to explore ways to deepen ties.

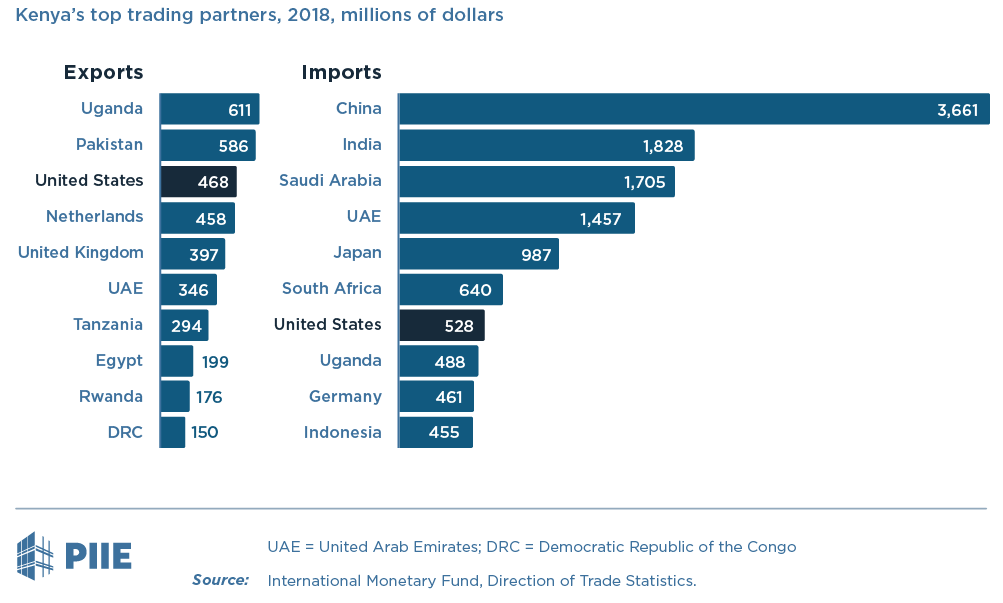

Yet despite this relationship, Kenyan trade with the US is relatively small and barely enough to place it among the US’ top 100 trading partners. In 2018, for example, annual total trade in goods between the US and Kenya was valued at about USD 1.1 billion. This placed Kenya as the 98th trading partner of the US; in contrast, the US was Kenya’s third-largest export market at the time. This discrepancy in trade has led many to argue that the proposed FTA is a largely symbolic manoeuvre by the US geared at neutralising China’s influence in Africa.

The FTA is also an important pathfinder for the post-AGOA relationship for the US. AGOA was enacted by the US Congress under the Clinton Administration in May 2000 and has since been renewed to 2025. The agreement was never meant to be permanent but a stepping-stone to a more mature trade relationship between the US and the continent. However, the trade and investment landscape in Africa has changed since AGOA came into force and last renewed in 2015. For instance, China’s growing economic influence in Africa and the conclusion of reciprocal economic partnership agreements (EPAs) between the EU and regional economic communities in Africa (RECs) have placed US companies at a disadvantage in Africa. These events have likely pressured the US Congress to protect American companies with an interest in Africa. As the renewal of the AGOA is at the discretion of Congress, and the extension of the present legislation is not guaranteed, the US is now likely to demand similar concessions that Kenya granted the EU in the EPAs.

Kenya’s motivations: Maintaining preferential market access to the US

Kenya’s main motivation for pursuing the FTA is to permanently secure the benefits it currently enjoys with the US under AGOA. The agreement has significantly enhanced market access to the US for qualifying Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, including Kenya which exports more than 70 percent of its products to the US duty-free under the Act. Securing permanent duty-free access to the US is a priority for Kenya, especially as the US has emerged as one of Kenya’s top export markets. While it was its third most important market in 2018, by March 2020, data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics indicated that the US had overtaken the Netherlands to become the second-largest market for Kenyan exports in the six months before September 2019. During that period, US imports from Kenya valued over USD 265 million compared to the Netherlands at over USD 250 million.

The failure to secure the FTA under such terms would place Kenya in a precarious trade position compared to other EAC countries should AGOA fail to renew. World Trade Organization (WTO) regulations, specifically the Enabling Clause, provides for a Generalised System of Preferences (GSP), which permits developed countries to offer non-reciprocal preferential treatment (such as zero or low duties on imports) to products originating from developing countries over the most favored nation (MFN) rates. The preference-giving country has the discretion to determine which countries and products to include in their schemes. Under the US GSP programme, exports from Least Developed Countries (LDCs) receive additional duty-free access to the US; however, Kenya is the only EAC country that is not designated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) as an LDC. Much of Kenya’s exports to the US (textiles and apparel) are therefore ineligible under the GSP scheme and are covered under AGOA only. As such, if AGOA is not renewed and Kenya does not secure the FTA with the US, other EAC member states will be at a strategic trading advantage with the US.

Kenya’s continental commitments

Challenges from the East African Community

Kenya is a member of the EAC, which oversees regional trade. Article 37 of the EAC Customs Union Protocol which refers to ‘Trade Arrangements with Countries and Organizations Outside the Customs Union,’ states that countries are only required to send the EAC Secretary-General the terms of any trade deal once it “intends to conclude or amend an agreement” with a third party for review and comments. As such, Kenya has not violated EAC law as the Protocol does not inhibit Member States from pursuing an FTA, as long as they notify the EAC for comments. However, what is left unanswered is the implication of the “comments” of the EAC Secretary-General as it is not clear whether the comments can override a deal with the third-party. The article is ambiguous and exposes some of the loopholes prevalent in African regional trade rules.

“Kenya’s seemingly unilateral decision to side-line the EAC is largely driven by its previous experiences in negotiations for joint agreements”.

Nonetheless, Kenya’s actions seem in contrast to Article 37 of the EAC Common Market Protocol which references the ‘Co-ordination of Trade Relations’ and calls on member states to “adopt common negotiating positions in the development of mutually beneficial trade agreements with third parties; and promote participation and joint representation in international trade negotiations.”

Furthermore, the establishment of the FTA directly contravenes the directive of the September 2019 Extraordinary Meeting of the Sectoral Council on Trade, Investment, Finance, and Industry (SCTIFI) that called on EAC Partner States to engage with the US at a regional level and with adequate consultations to preserve the integrity of the Customs Union.

Kenya’s seemingly unilateral decision to side-line the EAC is largely driven by its previous experiences in negotiations for joint agreements, in particular the EPA between the EAC and the EU. Though the EAC– EU EPA negotiations have been finalised, the agreement is incomplete as only Kenya and Rwanda signed it in 2016. Although the EU has granted Kenya interim duty-free market access, the lack of a complete agreement at the regional level threatened Kenya’s trading position. As already mentioned, Kenya is the only EAC country not classified as an LDC, and the failure to finalise the agreement would have been costly to Kenya compared to other EAC states. As LDCs, other EAC members would still have been able to access the European single market under the EU’s GSP scheme, or the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative, while Kenya would have lost preferential treatment.

Kenya has also faced hurdles to regional integration as the dominant economic power in East Africa, where, in 2018, it accounted for 51 percent of EAC GDP. Notably, regional integration in the EAC has faced significant challenges as member states have failed to agree on some key areas of integration, leading to the emergence of ‘coalition of the willing’– member states determined to proceed with integration despite objections from others – led by Kenya.

These past experiences have perhaps motivated Kenya’s current unilateral approach with the US although it is not the first time Kenya has bypassed the EAC. In 2016, Kenya, Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, and Rwanda resolved to ban the import of second-hand clothes, popularly known as mitumba, to protect their textile and leather industries. Following the EAC decision, the US Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles Association, a lobby group, argued that the ban would amount to a trade barrier and violate the AGOA. The US subsequently began issuing threats to EAC countries, warning that they would be suspended from AGOA benefits should the ban be imposed. Kenya ultimately conceded and pulled out of the ban in 2018 while Rwanda, Uganda, and Tanzania did not.

Challenges from the AfCFTA

The African trade integration landscape underwent a fundamental change with the coming into force of the Agreement Establishing the AfCFTA in May 2019. The agreement is meant to accelerate intra-African trade and boost Africa’s position in the global market by strengthening the continent’s common voice and policy space in global trade negotiations. It also requires State Parties to adhere to Article 4 of the AfCFTA Protocol on Goods, which calls for the extension of the same preferences to all State Parties. This means that any preferences accorded to the US would have to be extended to AfCFTA state parties on a reciprocal basis.

“Kenya is on the brink of becoming the first violator of the AfCFTA commitments before its fruition”.

Kenya is therefore on the brink of becoming the first violator of the AfCFTA commitments before its fruition. The AU has consistently recommended united negotiations amongst African nations on matters of common African interest with third-parties, such as trade and economic development.

At the AU summit in Nouakchott, Mauritania, in July 2018, and at the regular summit in Addis Ababa in January 2019, African heads of state agreed that no country shall enter bilateral free trade negotiations with a third party once the AfCFTA agreement comes into force, as they are likely to jeopardize the AfCFTA.

Implications for Kenya

While the launch of the AfCFTA has been pushed back to 1 January 2021, it remains unclear how Kenya intends to navigate the concerns of the EAC and its obligations under the AfCFTA as it pursues the FTA with the US. Nevertheless, its actions are likely to have consequences for its standing on the continent.

Firstly, the move erodes Kenya’s stature and standing as an advocate for Pan-Africanism and regional integration, and could ultimately impact Kenya’s trade with the region. Exports to Africa account for 40 percent of Kenya’s merchandise exports, compared to eight percent in the case of the US. Furthermore, Kenya’s exports to Africa are value-added products, which are critical to the success of its manufacturing industry and Kenya’s Vision 2030. Should Kenya pursue this deal with the US, its African counterparts in Africa may move to frustrate this trading relationship, likely through the implementation of non-tariff barriers (NTBs).

Secondly, Kenya may continue to lose the goodwill of the EAC and other African states in elective positions for key continental and international positions. Already relations with some EAC members, such as Tanzania, are strained and Kenya’s unilateral move confirms the reservations held by its peers. If Kenya learned something from its failed campaign to make its then foreign affairs Minister Ambassador Amina Mohammed Chairperson of the AU Commission in 2017, it was that its regional peers mistrust it. Kenya likely lost the bid to Ghana to host the Headquarters of the AfCFTA due to similar reasons.

A key position at stake is Ambassador Mohammed’s current bid for the Post of Director-General of the WTO after the sudden resignation of the current Director-General Robert Azevêdo. Decisions at the WTO, including the appointment of the Director-General, are concluded by consensus of the General Council, which consists of all WTO members. This implies that despite her impressive diplomatic career record, Kenya still needs to mobilise support from African nations who comprise 35 percent of the WTO developing country membership.

What are the alternatives?

For Kenya, there is a need to balance its historic relationship with the US with its African commitments. Kenya could explore the possibility of an EAC regional approach with the US in negotiations and thus safeguard the Customs Union Protocol and avoid a regional stalemate. As the FTA will serve as a model for future US – trade agreements with Africa, it may be feasible to work with other AGOA beneficiary countries to safeguard the opportunities under AGOA and secure a US-Africa FTA. This act would motivate regional partners to fast-track the ratification and operationalisation of the AfCFTA as well.

On the other hand, the US should appreciate the evolving landscape of regional integration in Africa and work with the AU to develop a framework for a continent-wide trade agreement. Hedging a deal against Chinese influence should not be the primary motivation, particularly as Africa’s relationship with China is only likely to grow.

(Main image: President Donald J. Trump meets with Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta Thursday, 6 February 2020, in the Oval Office of the White House – Tia Dufour/Official White House Photo)

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of SAIIA or CIGI.

Source: Africaportal.org

Read Also

- Senegalese President declares today a public holiday to celebrate AFCON win

- Fall in Love with Love at Banyan Tree Ilha Caldeira, Mozambique

- Ghana: The story of a coconut company that exports throughout the world

- Axim Government Hospital shuts two facilities to shoot Hollywood movie; residents cry foul

- Honoring Archbishop Desmond Tutu, An Advocate and Believer in Humanity

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.