By Yuh Acho / October 21, 2020

Dear Assembly of Heads of State and Government,

African Union General Assembly,

African Union Commission,

African Union Member States,

Today 21 October, commemorated yearly as the African Human Rights Day marks exactly thirty-nine (39) years since the adoption of the African Charter on Human and people’s Rights. But with the continent currently bleeding from different angles, I was wondering if this is not the best time to question our seriousness and dedication towards upholding the human rights cause in Africa?

Who could have believed that some of the biggest and fiercest battles and massacres would happen in the heart of this dreaded Covid-19 pandemic?

Not long ago, the world came together to protest against police brutality following George Floyd’s murder in the US. Many were those who completely saw it as a racial issue. While racial profiling was obviously at play, the merciless killing of unarmed and supposedly protected categories of persons by those with the mandate of protecting them throughout Africa puts the racial card to question.

The Lekki Massacre involving unarmed #ENDSARS# protesters on 20/10/20 in Nigeria only adds a litany of unfortunate and unnoticed encounters across the continent. What Nigeria is facing today is a longstanding normality of one of her closest neighbours.

These cases all involve specific elements of international crimes. Though States are expected to be the first prosecutors of such crimes, most of these cases never make it to Court and even if they do, the propensity of distrust towards our local jurisdictions is no longer a secret. So much so that in terms of human rights promotion and protection, it is now a battle pitting the State against its citizens.

At a high-level UN World Summit meeting in 2005, Member States committed to the principle of the responsibility to protect (R2P) according to which they would readily act to prevent and response to the most serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. The responsibility to protect embodies a political commitment to end the worst forms of violence and persecution. It seeks to narrow the gap between Member States’ pre-existing obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law and the reality faced by populations at risk of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. In one simple sentence, this means that the international community would be forced to intervene to protect civilians at high risk of a persecution from their government.

However, a category of Africans have always found their forte in castigating foreign military and judicial interventions within the confines of the R2P and the ICC, claiming Africa is able and capable of handling such issues on its own. The enthusiasm in this rhetoric is admirable to say the least; unfortunately, wishes aren’t horses.

On June 01, 1981 the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights was adopted and it entered into force on October 21, 1986. In its preamble the following are stated: “Considering the Charter of the Organisation of African Unity, which stipulates that “freedom, equality, justice and dignity are essential objectives for the achievement of the legitimate aspirations of the African peoples”; “Recognizing on the one hand, that fundamental human rights stem from the attitudes of human beings, which justifies their international protection and on the other hand that the reality and respect of peoples’ rights should necessarily guarantee human rights;”

Article 1 of this Charter obliges all Member States to recognise the rights, duties and freedoms enshrined in the Charter and shall undertake to adopt legislative or other measures to give effect to them.

Article 30 of this Charter creates the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights with mandate to promote and protect the rights, duties and freedoms enshrined in the Charter.

However, having rightly observed a need to also protect these rights through a judicial canal, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human And Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Ouagadougou Protocol) was adopted in Ouagadougou on June 10, 1998 and entered into force on January 25, 2004 with mandate to complement and reinforce the mission of the African Commission with jurisdiction over human and peoples’ rights violations.

This is where the real problem starts:

Firstly, as required by Article 34(3) of this Protocol, it took six (6) years for just fifteen instruments of ratification or accession to be deposited in order for the Court to come into force.

Secondly, once it came into force, it now faced the encumbrance of Article 34(6) of the Protocol which provides that the State shall make a declaration accepting the competence of the Court to receive cases from individuals and NGOs without which they cannot access the Court.

Twenty two (22) years since adoption, the status list shows that only thirty (30) State Parties have ratified it; amongst which only ten (10) have ever made the Article 34(6) Declaration. Sadly, between February 2016 and March 2020, four (04) of these ten (10) countries withdrew their declarations for various reasons leaving only Burkina Faso, Malawi, Mali, Ghana, Tunisia and The Gambia.

On 11 July 2003, just a year before the Ouagadougou Protocol entered into force, the Maputo Protocol was adopted by the 2nd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union and intended to be the principal judicial organ of the African Union under the appellation Court of Justice of the African Union. In its article 60, the Protocol stated that this judicial body was to go operational thirty (30) days after the instruments of ratification were to be deposited by fifteen (15) Member States. Just before this Protocol was to enter into force on 11 February 2009, the Sharm El-Sheikh Protocol was adopted.

The Sharm El-Sheikh Protocol was adopted on 1 July 2008 to merge the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the Court of Justice of the African Union into a single judicial organ called the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. This new organ was expected to enter into force thirty (30) days after fifteen (15) ratifications according to Article 9(1) of the Protocol. Twelve (12) years after its adoption, only eight (08) ratifications have been deposited.

Lastly, on June 27 2014 the Malabo Protocol was adopted as an amendment to the Sharm El-Sheikh Protocol specifically endowing the new African Court of Justice and Human and Peoples’ Rights with an original and appellate jurisdiction to try international crimes. This new organ was expected to enter into force thirty (30) days after fifteen (15) ratifications according to Article 11(1) of this Protocol. Sadly, six (6) years after, no single ratification has been deposited.

With the above elements I am still wondering, “is Africa truly able and capable”?

The most unfortunate and recurring clause in all but one (Maputo) of the above Protocols is the dreaded requirement for Member States to make an additional declaration recognising the jurisdiction of the Court and granting permission to their citizens to access these Courts. See Art. 9(3) of the Malabo Protocol, Art. 8(3) of Sharm El-Sheikh Protocol, Art. 34(6) of the Ouagadougou Protocol.

Even if adoption and ratification were not an issue, the obvious reality here is that, maintaining the above requirement simply means business would be as usual whatever the institution at play. Expecting violators to give victims permission to sue them in Court is simply illustration of hypocrisy and cowardice. Even if this is a standard practice in some international tribunals, can’t we copy innovatively to fit our own reality?

Who are we fooling?

Since we neither want military nor judicial intervention, don’t we at least need some spiritual intervention from some alien planet to teach us how to give life to the institutions we create? What is the objective of creating newer institutions when we know upfront that they are doomed to fail because we will not do what it takes for them to run effectively and efficiently?

It is clear that we are still in the epoch in which governments prefer showing off muscle through brutality and arrogance and paying lip service to the protection of our rights.

Our governments have used, abused and are still reusing us as they like with very little obstacles. After all, what can we do? Won’t we grumble and stay? They have power; they have the guns. This is an actual war of Sovereignty Vs Humanity. But again, is Sovereignty not meaningless if Humanity is useless?

Who are we really fooling?

In as much as I yearn for Africa’s rebirth, blowing optimism out of proportion is unwarranted. The reawakening is already long overdue but confronting our bitter reality is a condition sine qua non for this realization.

I wanted to say Happy Human Rights Day, but how can it be happy in blood?

Sincerely,

Bloody Human Rights Day!

©Yuh Acho

21/10/2020

Afrika,

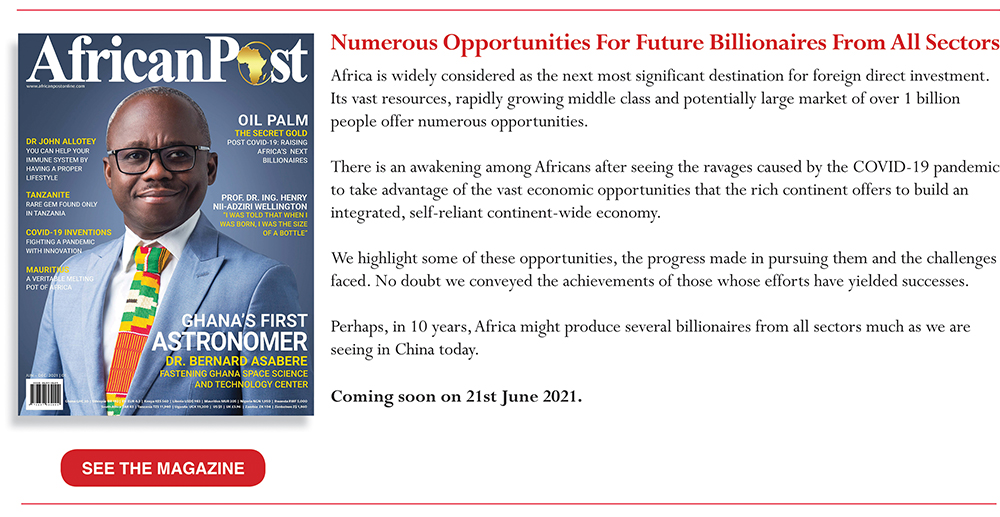

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.