The Bahamian pleasure palace featured a faux Mayan temple, sculptures of smoke-breathing snakes and a disco with a stripper pole. The owner, Peter Nygard, a Canadian fashion executive, showed off his estate on TV shows like “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” and threw loud beachfront parties, reveling in the company of teenage girls and young women.

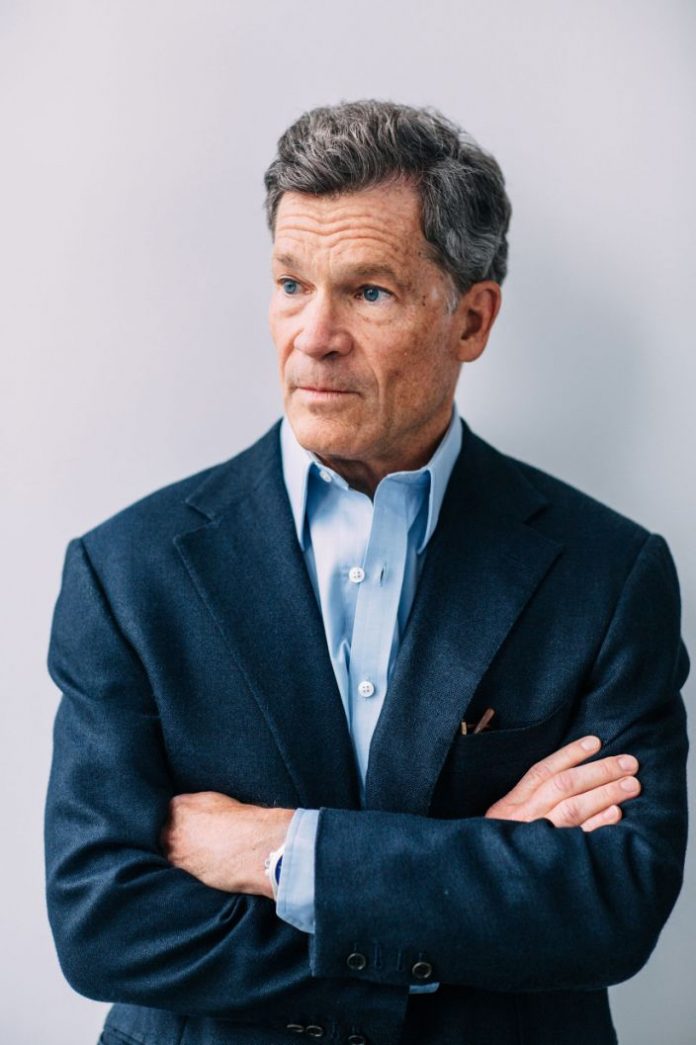

Next door, Louis Bacon, an American hedge fund billionaire, presided over an airy retreat with a lawn for croquet. Bacon preferred hunting alone with a bow and arrow to attending wild parties, and if mentioned at all in the press, was typically described as buttoned-up.

The neighbors had little in common except for extreme wealth and a driveway. But when Nygard wasn’t allowed to rebuild after a fire, he blamed Bacon. Since then, the two have been embroiled in an epic battle, spending tens of millions of dollars and filing at least 25 lawsuits in five jurisdictions. Nygard, 78, has spread stories accusing Bacon of being an insider trader, murderer and member of the Ku Klux Klan. Bacon, 63, has accused Nygard of plotting to kill him.

The latest charge is particularly incendiary: Lawyers and investigators funded in part by Bacon claim that Nygard raped teenage girls in the Bahamas.

This month, a federal lawsuit was filed by separate lawyers in New York on behalf of 10 women accusing Nygard of sexual assault. The lawsuit claims that Nygard used his company, Nygard International, and employees to procure young victims and ply them with alcohol and drugs. He also paid Bahamian police officers to quash reports, shared women with local politicians and groomed victims to recruit “fresh meat,” the lawsuit says. Through a spokesman, Nygard denied the allegations.

Over months of interviews with The New York Times, dozens of women and former employees described how alleged victims were lured to Nygard’s Bahamian home by the prospect of modeling jobs or a taste of luxury.

“He preys on poor people’s little girls,” said Natasha Taylor, who worked there for five years.

But this is not just a story of abuse allegations. It’s also a story about the lengths two rich men can go to in a small developing nation where the minimum wage is just $210 a week. Together, Nygard and Bacon are worth close to the annual budget of the government of the Bahamas, an archipelago off the coast of Florida with ritzy tourist resorts that belie the country’s pockets of poverty.

Their battle became a cottage industry for opportunists.

Investigators and lawyers tied to Bacon offered Nygard associates generous incentives to build an abuse case against the Canadian — Cartier jewelry, a regular salary or a year’s rent in a gated community, according to documents and interviews. Smaller payments filtered down to some accusers, which could be used to undermine their credibility in any court case or investigation.

Nygard used his wealth to intimidate critics and buy allies. He had employees sign confidentiality agreements and sued those he suspected of talking. Multiple women said he had handed them cash after sex, helping to buy silence. And he paid tens of thousands of dollars to people providing sworn statements to use against Bacon in lawsuits, according to court records, interviews and bank statements.

Some women said they felt exploited by both men — by Nygard for sex, and by Bacon against his enemy.

“They’re messing up people’s lives in the middle of their fight,” said Tamika Ferguson, who claims Nygard raped her when she was 16. She said she intended to join the lawsuit.

The Times interviewed all the women who eventually signed on to the suit, which identified them as Jane Does to protect their privacy. Reporters also spoke with five other women, who said Nygard sexually assaulted them in the Bahamas when they were teenagers. Three said they were under 16 at the time, the age of consent there. But two later recanted, saying they had been promised money and coached to fabricate their stories.

This isn’t the first time that Nygard, whose company sells women’s clothes at his own outlets and Dillard’s department stores, has been accused of sexual misconduct. Over the past four decades, nine women in Canada and California have sued him or reported him to authorities. He has never been convicted.

Nygard declined multiple interview requests. One of his lawyers said he had “never treated women inappropriately” and called the allegations “paid-for lies.”

Ken Frydman, his spokesman, denied all the claims.

Bacon, who founded New York-based Moore Capital Management, said he felt obliged to take action after hearing of possible sexual abuse by his neighbor. His associates have spent two years finding women to bring claims against Nygard.

“I of anybody knew what it was like to have this guy come at you,” Bacon said in an interview. “So my heart went out to these women.”

‘8th Wonder of the World’

Nygard’s property was unlike any other in Lyford Cay, one of the most exclusive communities in the Bahamas. His estate looked like something out of Las Vegas.

He called it the “Eighth Wonder of the World”: a lush retreat with sculptures of roaring lions and a human aquarium where topless women undulated in mermaid tails.

An avowed playboy who once joked that his attempt at celibacy was “the worst 20 minutes of my life,” Nygard wore his gray hair long and shirts open. He traveled with an entourage of models and women who described themselves as “paid girlfriends,” dated tabloid regulars like Anna Nicole Smith and fathered at least 10 children with eight women. Using himself as a human guinea pig, Nygard tried to fight off aging with stem cell injections and talked of cloning himself, one close friend said.

On many Sunday afternoons at his Bahamian estate, Nygard threw “pamper parties” that offered female guests free massages, manicures, horseback rides and endless alcohol. And he demanded a steady supply of sex partners, according to six former employees who said they recruited young women at shops, clubs and restaurants.

Eventually his staff compiled an invitation list, provided to The Times, with names of more than 700 women. Former workers said they photographed guests when they arrived, uploading the images for their boss’ perusal. Only those who were young, slim and with a curvy backside — which Nygard called a “toilet” — were supposed to be allowed inside, according to the ex-employees, including Taylor. (She asked to be identified by her maiden name to keep people from knowing her connection with Nygard Cay.)

Once the party got going, the former employees and girlfriends said, they coaxed teenagers and young women into Nygard’s bedroom, sometimes with the aid of alcohol and drugs.

Nygard, estimated to be worth roughly $750 million in 2014 by Canadian Business magazine, had long blended his professional and personal lives. He literally lived at work. A 1980 news article described an area of his office in Winnipeg — the city in Manitoba where he built his company — as a “passion pit” with a mirrored ceiling and a couch that transformed into a bed at the “push of a button.”

Over the years, he was repeatedly accused of demanding that female employees satisfy him sexually. There were the nine women in Winnipeg and Los Angeles who accused Nygard of sexual harassment or assault. But The Times spoke with 10 others who said he had proposed sex, touched them inappropriately or raped them. Only one of them is a plaintiff in the lawsuit.

Clash of the Titans

In 2009, a blaze erupted at Nygard Cay, damaging several cabanas, the grand hall and the disco. The fire department said it was accidental, probably caused by an electrical fault. But some Nygard Cay employees said their boss blamed Bacon, an ardent conservationist who had accused Nygard of illegally mining sand to create new beachfront.

The government refused to let Nygard rebuild. Within days, the war began.

Nygard sued over changes his neighbor had made years earlier to their driveway. Then he sued the government, saying it was colluding with Bacon to force him off the island.

Nygard was a formidable opponent. Police officers and local journalists dined at his home; one later admitted in court that Nygard had paid him to smear Bacon. Nygard also had allies in the Progressive Liberal Party, which he wanted to legalize stem cell injections. He bragged he’d given the party $5 million during the 2012 election campaign — legally, as the Bahamas has no campaign finance laws. After it won the election, a Nygard YouTube channel posted a video featuring six ministers visiting his estate.

But Bacon was a rare adversary. His wealth was valued at more than double Nygard’s.

He helped form a nonprofit called Save the Bays to target environmental abuses, starting with Nygard Cay. Fred Smith, a prominent human-rights lawyer, came on board.

Bacon and his older brother, Zack, hired a small army of lawyers and private investigators, including veterans of the FBI and Scotland Yard. They persuaded some of Nygard’s allies to provide evidence for a defamation lawsuit, filed in 2015. They launched their own lawsuits. And they paid well.

The Hunt

The Bacons said they were disturbed by stories they heard about Nygard having sex with teenage girls. In late 2015, they hired TekStratex, a new Texas security firm, to push American law enforcement officials to investigate him for sex trafficking.

The firm’s leader, Jeff Davis, told Zack Bacon that he’d worked for the CIA for 10 years — including in something called “the ghost program,” Bacon recalled.

Davis turned out to be a fraud. Instead of being an ex-spy, he was a former car broker with a string of debts and failed businesses. The Bacons had shelled out about $6 million. “I fired him,” Zack Bacon said.

He soon focused on a lawsuit, hoping to draw on the #MeToo movement and “the most aggressive lawyers in the world,” Zack Bacon said in a recording provided to The Times.

By last summer, Smith and the private investigators had introduced about 15 Bahamian women to American lawyers at the DiCello Levitt Gutzler firm. They were planning to bring a lawsuit in New York, where Nygard’s company had its corporate headquarters. His portrait hung outside a flagship store near Times Square, golden muscles flexing.

‘A Gift From Our Boss’

For years, Nygard had insisted that Louis Bacon paid people to lie about him. The hedge fund founder maintained that wasn’t true.

But his team created vulnerabilities, giving money and gifts to witnesses and accusers in the Bahamas, The Times found. Bacon and his brother said they were unaware of any gifts and payments, and expressed confidence in Smith’s professionalism.

The Bahamian lawyers and investigators were not paid by the Bacons directly. Instead, they were paid by a nonprofit Smith created, called Sanctuary, to support sexual assault victims; both he and Bacon donated generously to that.

“They are handing the defendant arguments,” said Jeanne Christensen, a New York lawyer focusing on sexual harassment.

The private investigators and Smith compensated two witnesses who found alleged victims: Litira Fox, a former girlfriend of Nygard’s who said she recruited for him, and Richette Ross, a former massage therapist at Nygard Cay who said she did the same. Through a spokesman, Nygard said that he did not remember Fox, and that neither recruited for him.

Accusers received smaller payments. Fox, who earned $2,000 a month, said she passed some of that to the women she brought to meetings with lawyers and investigators — often $200 for a visit. Smith acknowledged giving about $1,000 collectively to four or five alleged victims, but said that was for their time and expenses.

“I’m not going to give them $100 to lie, for goodness sake,” he said.

There were more substantial gifts. Deidre Miller said Fox invited her to the Baha Mar luxury resort in August 2018 to meet with investigators. She was a valuable witness — she would later tell The Times she had dated Nygard for years and had seen two teenagers in his bed, one in her school uniform.

Afterward, Miller said, the investigators took her and Fox to the resort’s Cartier store. There, she said, the men bought each woman a matching 18-carat gold bracelet and necklace for $9,350. Miller provided a photo of the receipt, though the man whose name was on it denied making the purchase.

“He was like, ‘It’s a gift from our boss,’” Miller recalled. “They said they were working for Louis Bacon.”

The New York Times

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.