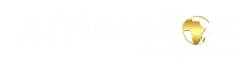

Achieving fame as a K-pop star involves years of intensive training, and often some plastic surgery. Euodias is one of the few British hopefuls to have experienced the gruelling life of a K-pop trainee. Here she describes what it was like, and explains why – after being selected for a girl group – she quit.

I was a child when I made the big move from my home in the north-east of England to South Korea, where I trained for two years to become a K-pop star.

At the time K-pop was largely unknown in Britain. But I’m half-Korean and half-Chinese, so I started watching South Korean TV dramas like Boys Over Flowers and Playful Kiss – and then fell in love with K-pop and the whole culture.

While my classmates were crazy about Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys, I was also listening to Wonder Girls and B2ST.

My burning ambition was to become an actor and perform.

One way of doing that in South Korea is to become an “idol”, which means someone who does everything: model, act, sing and dance. So K-pop seemed like a route to achieving my dreams.

From the age of 10, I auditioned for various companies in the hope that one of them would sign me up.

Often this meant sending a self-shot video of myself. Sometimes I skipped school to film an audition tape, which made my mum really mad.

Then, on a family trip to visit my grandma in Seoul, I got to go to a huge audition with more than 2,000 other hopefuls.

We were kept in a vast waiting room, like the sort you see on Britain’s Got Talent, except there were no chairs. So we sat on the floor in rows of 10.

After a six-hour wait, it was my row’s turn. My heart was beating so fast as we were called forward one-by-one.

When the first girl sang, the judge barked “Stop. Next!” before she got to the chorus of her song. Nearly everyone got the same treatment.

When it was my turn, I performed a monologue from a Korean TV drama. The judge stopped me halfway through.

“We’re looking for singers,” he said. “So will you sing?” I hadn’t prepared a song, but I had a go at doing A Whole New World from Disney’s Aladdin.

The judge halted me and asked to see me dance. I hadn’t prepared for that either, and felt like an idiot. So they put on a dance track and I did some freestyling.

After conferring with assistants, the judge gave me a yellow piece of paper. I was through to the next stage.

I was directed to a room where I was asked to walk along a line taped on the floor, and my face was photographed from different angles to see how I would look on camera.

Within days, I was asked to come back with a parent to discuss a contract.

Under the terms of the contract, I would leave my family and move to South Korea to live and train at the company.

The company could get rid of me at any time if it didn’t think I was good enough.

But if I chose to leave before the contract was up, I would have to repay the full cost of my training, which would run into thousands of dollars.

Mum reluctantly signed a two-year contract – the shortest they offered – on my behalf.

After the meeting we had an argument and mum didn’t talk to me for a month.

Soon after I started as a trainee, the entertainment company that had signed me up transferred my contract to another firm. Such moves are common and trainees don’t get any say in the matter.

My new company was strict. I had to live in their building with the other trainees who were all aged between nine and 16. The sexes were separated.

We only left the building to attend our normal school lessons. Korean trainees went to local state schools but because I was British I went to an international school. Other than that we weren’t allowed out without permission, which was usually refused.

If parents wanted to visit they had to get approval in advance. Relatives who turned up without notice were turned away.

On a typical day we trainees would wake up at 5am to get in some extra dance practice before school started at 8am.

When the school day ended we would return to the company to be trained in singing and dancing. Trainees would stay up practising until 11pm or later, in an attempt to impress instructors.

At night we were left to look after ourselves. We had a strict curfew to make sure we’d be back in the dorms before they locked up the building.

- Gangnam: The scandal rocking the playground of K-pop

- TXT: K-pop’s next ‘idol’ sensation?

- Inside China’s child pop star factory

Dating was banned, though some secretly did. Trainees were all supposed to act straight even if they weren’t. Anybody who appeared to be openly gay was ostracised by the company.

Both male and female trainees would have “managers” – uncle-type figures who would text us at night to keep tabs on us. If we didn’t text back, then we would immediately get a phone call, asking where we were.

There was no such thing as weekends or holidays. On national holidays like the Lunar New Year, trainees would remain in the company building while staff took the day off.

The company sorted us into two main groups, kind of like a Team A and Team B. I was one of the 20 to 30 members of Team A – we were thought to have the most potential.

Team B had around 200 trainees. Some of them had even had to pay their way into the company. They could train for years and years and never know if they would actually “debut” – the word used when someone is launched as a K-pop performer.

Team A trainees slept in dorms with four girls to a bedroom. The regular trainees would sleep together in a huge room and had to make do with mats on a wooden floor.

I saw exhausted Team B trainees sleep in the dance studios after training, because the mats there were just like the ones in their dorms.

I only ever saw one Team B trainee get promoted to Team A. If Team A trainees misbehaved, or complained about something they might be threatened with being thrown out or moved to Team B.

But generally nobody complained. We were all really young and ambitious. The company’s attitude was that everything we experienced was part of learning the discipline needed to be a K-pop idol. So we just accepted everything.

Inside the company building, we didn’t use our own names, except with other trainees. We were each given a number and a stage name in keeping with the sort of character they had picked for us.

I was given the name Dia, but our instructors would only ever call us by our numbers, which they read from stickers on our shirts. It felt weird, a bit like we were in some sort of science experiment.

End of Instagram post by euo.coeur

I knew I had the attributes to be a successful idol.

The company favoured me, because I am very small – instructors constantly praised me for being petite. Don’t get me wrong, I love eating, but I’m lucky to have a high metabolism and don’t gain weight easily.

Weight was the constant obsession of everyone there. Everyone was required to be no heavier than 47kg (7st 6lb or 104lb) regardless of their age or height.

At weekly weigh-ins, your body would be analysed by the trainer, and then they announced your weight to everyone in the room.

If you were over the designated weight, then they would ration your food. Sometimes they would even take away entire meals and those “overweight” trainees would just be given water.

I thought that was really harsh because some of those girls couldn’t help being tall.

Starving yourself was really normalised. Some trainees were anorexic or bulimic, and many of the girls didn’t have periods.

It was common to pass out from exhaustion. Often we had to help carry unconscious trainees back to the dorms.

I passed out twice during dance practice, probably because I was dehydrated or hadn’t eaten enough. I woke up in bed not knowing how I got there.

The attitude among the trainees after that was like, “Good for her! She wants it so much!” Looking back on it now, I think it was really disgusting.

I found that I didn’t really have good friends there, everyone was more like a colleague. The environment was way too tense and competitive to forge real friendships.

The stressful atmosphere was heightened by the monthly showcase events. Each trainee would perform in front of everyone and be evaluated by the instructors.

If a trainee didn’t get a good grade, then they would be kicked out immediately.

They would be replaced by a constant stream of new arrivals. What was even more intimidating was that some of the new trainees had already had plastic surgery done, so they already looked more like K-pop stars than the rest of us.

There was also bullying going on among the trainees. One girl was picked on because she was over the maximum weight. Another trainee who was a good dancer had his dance shoes stolen.

I missed my old friends back in England but I couldn’t really keep in touch with them as instructors made us hand in our phones so we would focus on our training. The company also wanted to make trainees seem more mysterious before they debuted, and didn’t want us posting anything embarrassing on social media.

We could get our phones back for 15 minutes at night, and I would use that time to call my mum. But most trainees also secretly kept a second phone.

My parents knew that training was difficult, but there really wasn’t much they could do because I was under a contract and they were so far away. Most of the Korean trainees wouldn’t tell their parents anything at all because they didn’t want them to worry.

What kept me going was the belief that I would eventually debut as a member of a group.

However, the company only had spots for fewer than half of the members of Team A. We competed for them through constant examinations in singing, dancing, and interviews.

K-pop groups are typically organised like this: a lead vocalist, dancer, rapper, youngest member, etc. Everyone has a specific role.

I was delighted when they told me I had been picked to be a lead singer. But then the company said they were considering me for an alternative role in the group, the visual.

End of Instagram post 2 by euo.coeur

The visual is the face of the group. You get picked for this because of your appearance, and crucially, how you might look in the future. Another girl was in competition with me for this spot.

She was naturally more attractive than me, but the company predicted that if I got plastic surgery I would end up prettier than her and would then be ready to be the visual.

By Korean standards I have a very big face, so they wanted to change the bridge of my nose and shave my jawline.

The company couldn’t force a trainee to have plastic surgery, but it was strongly encouraged. Plastic surgery is very normal in South Korea and the prospect of having surgery didn’t bother me at all. I saw it as an investment in my future – the cost of the operation would have been added to my debt to the company.

But my mum had mixed feelings, she realised it meant I would be closer to becoming an idol, but she was also worried for me.

When the company told me that I was being lined up for the visual spot, I was so happy.

They told me that I was going to be a K-pop star, and that’s really amazing to hear, especially when you’re an impressionable teenager hearing that from powerful people.

As time went on, the company started to tell us more about what the group was going to be like.

They told us the music genre, the style that we would have, and I started feeling iffy about the whole thing.

I learned about the character behind my stage name, Dia. She was supposed to be very reserved, sweet, and innocent. As the visual, I would be expected to personify those characteristics.

But Dia just wasn’t me. I’m opinionated and loud. I doubted I would be able to keep up this docile personality in public.

End of Instagram post 3 by euo.coeur

I thought it might just be worth it if it led to me becoming an actor. But when I tried talking to the company about my ambitions the response was: “No, we think you’ll fit better with this girl group.”

Someone senior there told me that as I was half-Korean, if I pursued an acting career then the best I could hope for was a supporting role on a TV show.

I felt my dreams slipping away.

My contract came up for renewal before my group was due to be launched – and I said that I wanted out.

It’s really unusual to walk away, most trainees want the dream so badly that they’ll agree to anything.

Despite my refusal, I parted on good terms with the company.

Because I left when I did, I had no debts to pay off, I had fulfilled my part of the contract.

If I had stayed and debuted with the group then I would have been charged for the cost of my instructor fees, accommodation, and for any plastic surgery.

Even successful acts have to continue working to pay off all the debt incurred during training, and the new debt that builds up when you’re an idol. It’s actually really difficult to make money by being a K-pop star.

I returned to England without having had any plastic surgery and was reunited with my old friends. I was able to sit my exams with everyone else.

I went on to do an art foundation course and then got a place at a fashion school in France. I’m really fortunate because so many trainees get dropped at 18, or finish their contracts when they’re 21 and feel lost. They gave up everything to try to be a K-pop idol, but that’s ended and they find themselves with no qualifications.

My mum was so happy that I was back. She always believed training wasn’t the right thing for me. But she knew I had to find that out for myself. I had to go the long way round, but I learned that mum is always right.

When I see videos of the group I was to have been in, I feel relieved that it isn’t me up there on stage.

The whole thing feels fake to me, as I know those girls personally, and the way they have to behave in public is not what they are like in real life.

I’m not really thinking about pursuing acting at the moment, except perhaps as a hobby.

Instead I have a career as a YouTuber. I’ve realised that I’m quite entrepreneurial.

I love making videos for my channel. I find I’m applying a lot of what I learned in my K-pop training. I feel liberated because I control everything, from planning to filming to editing.

The more I think about it, the more I think I made the right decision.

As told to Elaine Chong

Since Euodias underwent her training the South Korean Free Trade Commission has introduced regulations to ban some unfair practices in contracts between K-pop trainees and entertainment companies.

BBC

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.