Images tell a story and form opinions. We unconsciously rely on images to form our view, particularly when we haven’t visited a place. A large part of our perspective on other civilizations is based on stereotyped images. A photo does not only portray the other; it also defines us in relation to the ‘other’.

Representations have the ability to trick us into thinking we know something with which we have no first-hand experience. Such images can form public opinion, and this can then be exploited into creating particular policies.

The purpose of this paper is to examine why we only have one story about ‘Africa’, based on such images; why Africa is portrayed as a tribal, underdeveloped region that deserves our aid and assistance.

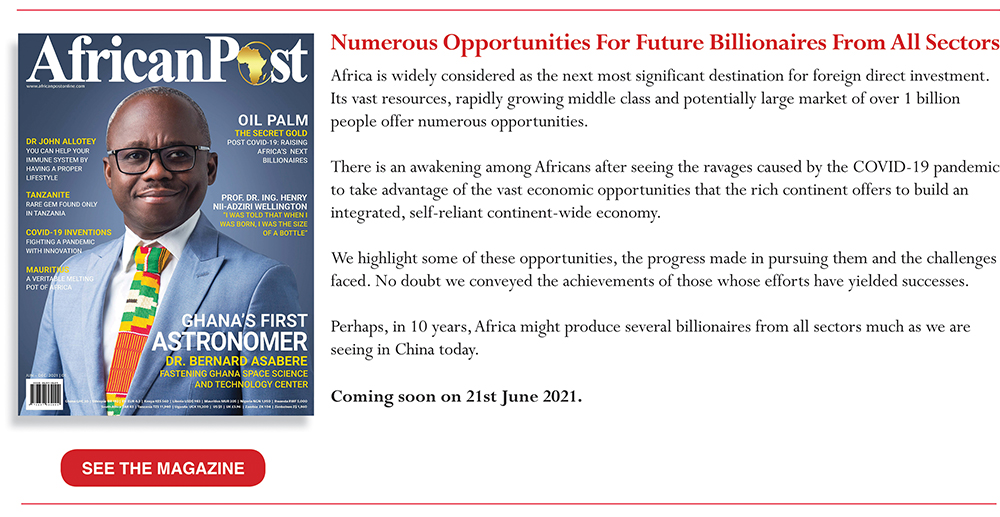

Why is Africa constantly portrayed with the unvarying image of the rural African hut, rather than with a photograph of housing blocks and skyscrapers which are part of urban life in the continent today? Why are we constantly showered with images of extreme poverty, rather than representations of the vivid entrepreneurialism, impacting the lives of millions today?

Or, instead of seeing the demands made by professional associations or workers’ syndicates in fast-changing cities, we continue to see the desperate plea of an isolated, sick or ‘hungry’ child in a remote village.

The main reason for the continued dominance of this ‘one story’ is the humanitarian and development industry. In the past few decades, the world has seen an explosion of NGOs, which means that there is fierce competition amongst them for funding. The idea is that if you are not negative enough in your portrayal, you won’t get funding. So fierce is the competition, in fact, that many NGOs don’t want to hear good news. And, in the end, they dehumanize the people they are supposed to be helping.

Exaggerations of desperation are the rule. The stories we get are full of sensationalism and dramatization. Western journalists rely on international NGOs in order to gain access to areas but also to obtain information on a crisis. In turn, humanitarian organizations refuse to cooperate if they are not shown in a positive light. The contrast between the poor black child and the active white savior forms mentalities that are extremely difficult to change.

Particular statistics, and especially images, are selected in such representations in order to present African societies as more or less failing to modernize. African traditions and customs are glorified as exotic. Journalists and photographers alike seek to capture the dramatic and the exceptional, which results in superficial coverage.

The implicit message of development photography is that, without western aid, societies in the developing world cannot support themselves. This is a deeply racist belief, which has its roots in the European colonialist discourse.

Such portrayals of the region have been rightly named ‘development pornography’. It is based on a kind of perverse enjoyment triggered in people when they view someone suffering. Europeans who are currently facing shrinking incomes will likely perceive their own lives as brighter when compared to biblical images of famine and war.

What developing countries really need is investment. Yet investors do not see Africa as worth investing in. NGO portayals destroy confidence that Africa offers economic opportunities. And without job creation poverty will remain. NGOs who promote a message about ‘ending poverty’ are simultaneously scaring off those who have the ability to end poverty and the evils that accompany poverty. The continent will not attract significant foreign capital if global media continue portraying the region as a place of need and desperation. Capital will only start flowing into the region if it is seen as a place of potential and opportunities. Exaggerated images of instability negatively affect tourism as well.

Humanitarian and development agencies have developed their own survival instincts in a changing global economic landscape. And they use negative images to sustain their work. They are very well aware that positive images and stories, or simply a realistic portrayal of Africa today, will endanger their career their jobs.

Cheap, predictable, stereotypical images satisfy the self-pleasing fantasy of aid workers, and it ensures the enduring domination of Western countries over the countries of the Global South.

The Guardian, using data delivered by a coalition of UK and African equality and development campaigners, stated in a 2017 report that “more wealth leaves Africa every year than enters it – by more than $40bn (£31bn) – according to research that challenges ‘misleading’ perceptions of foreign aid”.

World-is-plundering-africa-wealth-billions-of-dollars-a-year

In another report in the Guardian stated that “Africa is losing £192bn to the rest of the world each year, while only £134bn flows in. This means Africa suffers a net loss of £58bn a year. […] And against the £192bn annual losses, aid puts back less than £30bn. It’s a tiny part of the picture – and clearly no solution to the regular and systematic impoverishment of a continent.”

Africa-rescue-aid-stealing-resources

Actual figures highlight the dishonesty of the aid narrative which portrays Africa as the grateful beneficiary of the rich world’s generosity. Benevolent and well-meaning aid workers, who still exist, need to understand that to reinforce this perception or to fail to challenge it is to perpetuate a lie and one that causes profound damage to the cause of eradicating poverty.

Africa subsidizes the western world and not the other way around. The real struggle is to stop these enormous losses that drain the continent of its resources. Justice for Africa requires action to stop the resources being taken out.

The continent has no microphone of its own. An African Aljazeera does not exist. We do not hear from the growing urban middle classes who are challenging the old perceptions and power relations. Our fantasies still thrive on imagined communities and imagined geographies. Africa is still, to the mind of many, a vast landscape of jungles and deserts. We still use the ‘poor other’ to define ourselves which leads to internalized racial superiority.

NGOs have become identity entrepreneurs. They shape how people see themselves in the West but also in the developing world. They separate ‘competent’ and wealthy donors from dependant victims. In this way, they create identities. Such divisions cause the internalization of self-hatred for several races and ethnic groups.

Within this culture of aid giving, there are now several ‘experiences’ offered to wealthy westerners in the Global South. Voluntourism and other ‘poverty experiences’ exist primarily to satisfy volunteers, not the purported beneficiaries. Volunteer opportunities add value and social capital to Westerners’ CVs, while allowing aid workers to act as if their field sites are their own private playgrounds.

What we need is structural economic change and not charity.

Personal Encounters

My first negative experience with the hypocrisy of the humanitarian sector occurred while I was working for a British NGO in Ethiopia.

One day, a PR specialist came from London to do a promotional photo shoot. She demanded that a female beneficiary act pregnant for the shoot, by asking her to put a pillow underneath her shirt. She then instructed her to jump on a broken stretcher, which she had other beneficiaries carry. The photo was taken, and the caption was meant to state that this stretcher was donated to pregnant women in this particular village.

At the time I was young and quite naïve. Thus assumed that I was simply unfortunate to choose a hypocritical NGO. Years later, after having worked for a much larger, well-known, and very respected organization, I realized that such behavior is intrinsic to the sector.

Yet, despite the hypocrisy, widespread corruption and inefficiency of the sector, I consider the gravest fault to be its irrelevance. The activities and services offered by NGOs are usually totally unrelated to the actual needs and demands of beneficiary communities.

(Icrc-hypocrisy-in-myanmar-and-the-democratic-republic-of-congo )

The largest and most successful NGOs have the power – and the funds – to employ communication and media professionals of the highest rank, and thus have a potent media presence, and great influence on international audiences.

After I quit working for such a powerful international organization, and decided to publish an article detailing the ways in which they failed the communities they were supposed to be helping, I realized the unimaginable extent of their influence on the media. In the first instance, they didn’t allow the publication of a section of my article in Myanmar Times. ngos-do-more-harm-good-conflict-zones

In the second instance, when I decided to write for South Africa’s Mail and Guardian about these revelations, my article’s publication was delayed for several months as the newspaper made sure that they wouldn’t be sued for publishing it. The head of public relations at the International Committee of the Red Cross replied to my article.

After the first publication in Myanmar Times, I was threatened by my former employers, with an email stating that if I don’t remove the articles I would be sued. Quite typical for ICRC doing one thing in public – replying to both articles of mine – but privately threatening to sue me.

Menelaos Agaloglou was Protection Delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Kachin State in Northern Myanmar, and in Kasai State in the Democratic Republic of Congo (2016-2018).

Previously, he was the Head of Geography and Economics Department in the International Division of the Greek Community School in Addis Ababa (2011-2015).

He is a researcher at the Center of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (CEMMIS) at the University of Peloponnese in Greece.

He has covered the civil was in Libya and the revolution in Egypt (2011) for Think Africa Press.

He has taught Conflict Resolution and English in the University of Hargeisa in Somalia and Social Studies at the Ahmadiyya elementary school in Sierra Leone.

He has travelled throughout western, central and eastern Africa and carried out a research for a British NGO in Silla Village, Mauritania.

His BA studies were on Politics with Business at Queen Mary, University of London, and his MSc was on Globalization and Development at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. He speaks English, French and Greek.

He has served in the Hellenic Army.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect African Post Online editorial stance.

He is a researcher and has traveled throughout Western, Central, Eastern Africa, and Greece. He has covered the civil war in Libya and the revolution in Egypt (2011) for Think Africa Press. He has taught Conflict Resolution and English. Menelaos Agaloglou has a BA degree in Politics and Business at Queen Mary, University of London, and MSc in Globalization and Development at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.