It began in the East. At least, that’s what the experts think. Maybe it came from animals. Maybe it was the Chinese. Maybe it was a curse from the gods.

One thing is certain: it radiated out east, west, north, and south, crossing borders, then oceans, as it overwhelmed the world. The only thing that spreads faster than the contagion was the fear and the rumors. People panicked. Doctors were baffled. Government officials dawdled and failed. Travel was delayed or rerouted or aborted altogether. Festivals, gatherings, sporting events—all canceled. The economy plunged. Bodies piled up.

The institutions of government proved very fragile indeed.

We’re talking, of course, about the Antonine Plague of 165 CE, a global pandemic with a mortality rate of between 2-3%, which began with flu-like symptoms until it escalated and became gruesome and painfully fatal. Millions were infected. Between 10 and 18 million people eventually died.

It shouldn’t surprise us that an ancient pestilence—one that spanned the entire reign of Marcus Aurelius—feels so, well, modern. As Marcus would write in his diary at some point during this horrible plague, history has a way of repeating itself. “To bear in mind constantly that all of this has happened before,” he said in Meditations. “And will happen again—the same plot from beginning to end, the identical staging. Produce them in your mind, as you know them from experience or from history: the court of Hadrian, of Antoninus. The courts of Philip, Alexander, Croesus. All just the same. Only the people different.”

This pattern of disease is nauseatingly familiar. It’s a pattern that has repeated itself like a fractal across history. Indeed, we could be talking about the Bubonic Plague (aka the Black Death), the Spanish Flu of 1918, or the cholera pandemics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, just as easily as we are talking about the Antonine Plague and thinking about the coronavirus pandemic that is spreading across the globe. As Marcus would say, all we’d have to do is change a few dates and names.

It can be a very jarring mental exercise for some—thinking about the way the history of disease repeats itself—because we like to view the evolution of human civilization as moving inevitably in some new, unique direction. We like to see history as a steady progress. Then when bad things happen, when catastrophe strikes, we feel like the world is coming apart. We suffocate ourselves with breathless shouting about the sky falling and give ourselves heart attacks over not being prepared for what is to come.

It’s the same story, unfolded as if from an ancient script, written on the double helix of human DNA. We make the same mistakes. Succumb to the same fears. Endure the same grief and pain… then eventually exult in the same heroism, the same relief, and hopefully, the same kind of emergent leadership.

And that, really, is the key to survival, to persevering for the better: Just because history repeats itself is not an excuse to throw up your hands and give yourself up to the whims of Fortune. The Stoics say over and over that it is inexcusable not to learn from the past. “For this is what makes us evil,” once wrote Seneca, who lived two generations before Marcus and watched Rome burn. “We reflect upon only that which we are about to do. And yet our plans for the future descend from our past.”

So what can we learn from the Antonine plague? What can we find—in ourselves, in other people, in the lessons of the past—that can guide us today as the reality of this current pandemic crisis sets in?

First, we should count our blessings. We’re lucky that the coronavirus (COVID-19) is but a sneeze compared to the bubonic plague which killed 25 million people in just a few months in the sixth century, or smallpox which consistently killed some 400,000 people every single year of the eighteenth century, or when measles killed 200 million people in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, or when the Spanish Flu claimed 50 million souls in 1918. Indeed, precisely what so worries scientists about COVID-19 is actually a blessing: The disease is particularly contagious because it doesn’t quickly debilitate and kill most of its victims. No one with an active case of SARS was playing shuffleboard on a cruise ship or skiing in the Alps. They were suffering until death within hours.

We should count our blessings, but we should not count ourselves lucky—at least not in equal measure. We have to make our own luck, as all survivors do. If Marcus Aurelius had his choice, he would not have chosen to lead in crisis. In fact, he wouldn’t have chosen to lead at all. He wanted to be a philosopher, not emperor. And that was “the essential tragedy of Marcus Aurelius,” biographer Frank McLynn wrote. “No man could have been less equipped to deal with the crisis that now broke over the empire.”

Yet, like all great heroes, he surprised everyone by rising to the occasion. He had no ego, and had a keen eye for surrounding himself with brilliant public servants. As McLynn explains, Marcus Aurelius’s “shrewd and careful personnel selection” is worthy of study by any person in any position of leadership. He searched for and brought in the best. He broke the mold and filled his staff with talent, not aristocrats or cronies. He actually listened to advice. He empowered people to make decisions. He hired Galen, the most famous physician and polymath of antiquity, to lead medical lectures and anatomy demonstrations, wanting to elevate “the intellectual tone” of his court. It was Galen who he empowered to lead the efforts to combat the plague, the smartest medical mind of his time.

Once his team was in place, Marcus shifted his focus to the growing economic crisis. Longstanding debts owed to the government were cancelled. Fundraising efforts began with a masterstroke of inspirational leadership. As McLynn writes, Marcus “conducted a two-month sale of imperial effects and possessions, putting under the hammer not just sumptuous furniture from the imperial apartments, gold goblets, silver flagons, crystals and chandeliers, but also his wife’s silken, gold-embroidered robes and her jewels.” Funerals for plague victims were paid for by the imperial state. Reluctantly but unavoidably, Marcus Aurelius also confiscated capital from Rome’s upper-classes, knowing that they could afford to pay. He also audited his own officials and allowed no expenditures without approval. In a crisis, people must trust that their leaders are doing the right thing and that they are bearing the same burden as the citizens—if not a greater one.

It would be difficult to overstate the fear that must have pervaded the empire. The streets of Rome were flooded with corpses. Danger hung in the air and lurked around every corner. Knowing little about the spread of germs or disease, prone to superstitions, waking up each day must have been terrifying for children and adults alike. Romans burned incense which they thought could keep them safe, instead it blanketed the city in thick smoke and odors, which mixed in with the smells of the recent dead and a city in lockdown.

Certainly, no one would have faulted Marcus if he had fled Rome. Most people of means did.

Instead, Marcus stayed, at enormous personal cost. He braved the deadliest plague of Rome’s 900-year history, never showing fear, reassuring his people by his very presence.

He was Churchill during the Blitz, inspiring the people to keep calm and carry on, except instead of lasting for a few months, he endured the siege for years without complaint. Even as he lost several young children and his fortune dwindled away.

He was not Xi Jinping, who is rarely seen in public. He locked down his citizens, but he did not lock them out. His doors were always open. He summoned priests of every sect and doctors of every specialty and toured the empire in an attempt to purge it of the plague, using every purifying technique yet known. He attended funerals. He gave speeches. He showed up for his people, assuring them that he did not value his safety more than his responsibility.

In this he was the perfect embodiment of what “stoicism” means to us today. He didn’t get rattled. He didn’t panic. He kept himself strong for others. He insisted on what was right, never what was politically expedient. He was resolute.

That’s not to say he was delusional, or that he reassured the people with false hope or misleading numbers, as some leaders have. In fact, Marcus was deeply moved by the suffering of the people. We are told quite vividly by historians of the sincere weeping of Marcus Aurelius in public after he overheard someone argue, “Blessed are they who died in the plague.” A good leader is strong, but feels deeply the pain of others.

In 180 CE, having led the people through the worst of the crisis, which stretched on for some 15 years of his reign, and having never hidden or neglected his public duties, Marcus Aurelius began to show symptoms of the disease. It was a fate that was inevitable given his style of leadership. By his doctors’ diagnosis, he knew he had only a few days to live, so he sent for his five most-trusted friends to plan for his succession and to ensure a peaceful transition of power. Bereft with grief, these advisors were almost too pained to focus. “Marcus reproached them for taking such an unphilosophical attitude,” McLynn writes. “They should instead be thinking about the implications of the Antonine plague and pondering death in general.”

“Weep not for me,” began Marcus’s famous last words, “think rather of the pestilence and the deaths of so many others.”

It is here that the past provides its most powerful and sobering lessons. Far too often, the first time civilizations realize just how vulnerable they are is when they find out they’ve been conquered, or are at the mercy of some cruel tyrant, or some uncontainable disease. It’s when somebody famous—like Tom Hanks or Marcus Aurelius—falls ill that they get serious. The result of this delayed awakening is a critical realization: We are mortal and fragile and that fate can inflict horrible things on our tiny, powerless bodies.

There is no amount of fleeing or quarantining we can do to insulate ourselves from the reality of human existence: memento mori—thou art mortal. No one, no country, no planet is as safe or as special as we like to think we are. We are all at the mercy of enormous events outside our control, even (or especially) when that enormity arrives on a wave of invisible, infinitesimally small microbes. You can go at any moment, Marcus was constantly reminding himself and being reminded of the events swirling around him. He made sure this fact shaped every choice and action and thought.

Be good to each other, that was the prevailing belief of Marcus’s life. A disease like the plague, “can only threaten your life,” he said in Meditations, but evil, selfishness, pride, hypocrisy, fear—these things “attack our humanity.”

This is why we must use this terrible crisis as an opportunity to learn, to remember the core virtues that Marcus Aurelius tried to live by: Humility. Kindness. Service. Wisdom. We can’t waste time. We can’t take people or things or our health for granted.

Even if we may now lack the kind of sacrificial leadership who can show us the way by example—we can turn to the past to tell us what that leadership looks like and to teach us about all these things we must cherish.

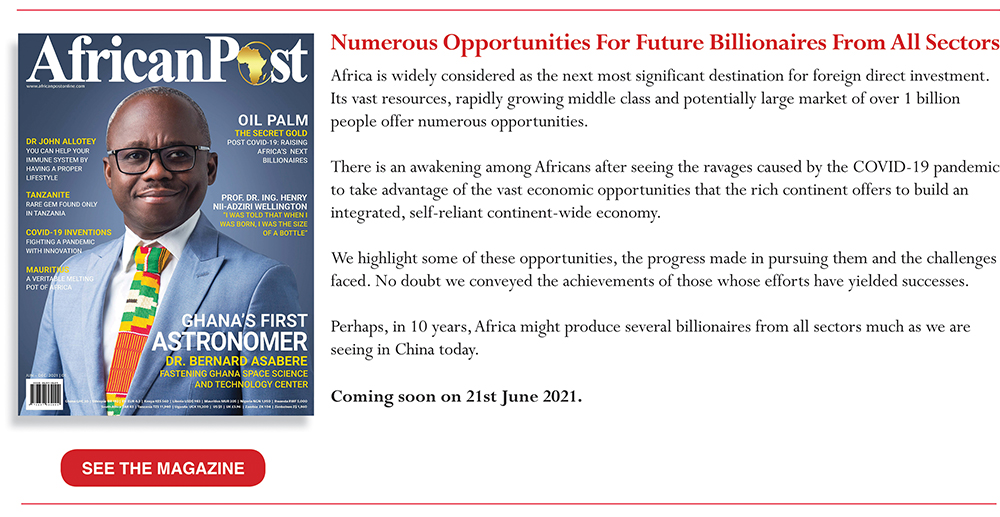

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.