I believed I was helping an honorable, decent man — until he was released from prison

I played a vital role in helping a man, once sentenced to life without parole (LWOP), in getting a commutation from the governor and then released. It is safe to say that without my tireless efforts and tremendous support, he would still be in prison today.

I knew him for nearly 15 years while he was in prison and believed he had become a good, decent, and honorable man, one who was redeemed and rehabilitated. We worked side by side on important prison reform/LWOP abolition projects, he from within his cell and me in the free world, carrying out work that was simply impossible given the confines of prison. I helped him financially, paid for lawyers, ensured he received life-saving medical care when he was seriously ill, and treated him in all respects like a beloved brother. (I have no other family, so his role as my brother was huge in my life.) We spoke on the phone daily, ending each call with “Love you, bro” and “Love you, sis.” I was greatly anticipating continuing our work together after his release, being introduced as his sister, and acknowledged for my contributions to our cause, which were kept hidden during the time he was incarcerated for fear of shutdown by unsympathetic prison administrators.

Sadly, that was not to be.

After he was found suitable for parole, his attitude toward me changed. He became distant and aloof but begged me for “patience” because he was overwhelmed about rejoining the free world after so many years of imprisonment. I believed this and remained supportive, despite enduring increasingly insensitive and sometimes downright hateful treatment, greatly out of character for the person I had known for so long. Interspersed with this, though, were just enough moments of kindness and connection, which prevented me from seriously considering ending our relationship and with it, my assistance.

For he still needed things from me once he was out: a loan for a laptop and driving lessons to enable him to get his license. He also needed time to permanently disentangle the myriad ways our lives were interconnected so he could make a clean break.

A few weeks after his release, I had major surgery and was close to death with life-threatening complications. The doctors told my friends I might not survive, and they should call anyone who may want to say goodbye. One of them called my brother.

He was already coming to the hospital to visit another patient and stopped by the intensive care unit briefly, just as I had been taken off life support. My friends were horrified by his demeanor; he spent much of the time talking about himself and how he was being pursued by literary agents and Hollywood producers for book and movie deals because of his extraordinary transformation and miraculous release from prison. He barely mentioned my illness and never asked to speak with any of my doctors about my condition and chances for survival.

I never saw him again. Once he had everything he needed from me, he threw me away like a piece of trash even as I was facing my death.

“I saw a way to get what I wanted, and I went for it,” he replied. “I’m very sorry. I promise it won’t happen again.”

I can only speculate about my brother’s reasons for leaving me behind in such a cold-blooded way. I am reminded of one situation which may hold some clues. Many years ago, my brother asked me to smuggle tobacco into the prison, which I refused to do. Then, the following week, I was astounded to see a colleague of mine, who had been present at the original conversation and witnessed my refusal, pull a wad of tobacco out of his shoe and hand it to my brother.

I cut off all communication with my brother for some time after that. When we finally spoke, he admitted he had gone behind my back and pressured my colleague, a meek, mild-mannered man who had difficulty saying no. “Why would you do something like that?” I demanded.

“I saw a way to get what I wanted, and I went for it,” he replied. “I’m very sorry. I promise it won’t happen again.”

My brother’s words about this incident keep reverberating in my mind: I saw a way to get what I wanted, and I went for it. This brilliant man, an astute observer of human nature, knew just how much I needed a family, an intellectual peer, and a collaborator in a noble cause. I believe he played these roles in a meticulously calculated, insidious manipulation for as long as necessary to get what he needed from me. I was a means to an end, nothing more. I have no doubt, had he not been released, we would still be talking on the phone every day, ending our calls with “Love you, bro,” and “Love you, sis.” I also have no doubt I would still be spending thousands of dollars every year making sure his life in prison was as comfortable as possible.

I remained seriously ill for a very long time. As I recovered, I had to make a decision about what to do with all the years I had invested in working to end LWOP. Part of me wanted to turn my back on all of it since the issue of LWOP had become inextricably linked with the agony of my brother’s betrayal.

Since then, I have struggled to come to terms with what happened and to conduct myself honorably and with dignity in the face of unspeakable cruelty. Ultimately, I realized I still believed LWOP was inhumane, and I could not allow the actions of one heartless man to force me to turn my back on the thousands of people sentenced to die in prison. They should not be judged by my brother’s callousness and lack of integrity. I chose to continue my work to end LWOP.

This experience has given me a much deeper understanding of the suffering of many of the families of the victims of those serving LWOP, especially when the person who has caused such terrible harm shows no remorse. It pains me to admit that when my focus was on securing freedom for my brother, I had little to no awareness of the effect that our campaign had on victims’ families.

Now, I have enormous compassion for the anguish these families must endure to hear the LWOP abolitionists cry, “Bring them all home!” or to see the face of their loved one’s killer on T-shirts at rallies. I feel exactly this way when I read how my brother speaks nationwide at universities and law schools as an authority on prison and sentencing reform, never mentioning my name and erasing our work together and my role in his release as though I never existed.

Ending LWOP does not mean everyone will, or should, get out of prison, only that they will have a chance to go before a parole board. Occasionally, people devoid of conscience, like my brother, may be able to manipulate their way out by convincing those involved in the parole process that they are rehabilitated and do not pose a danger to society. In a 2009 Canadian study, co-author Robert Hare, PhD (the world’s foremost authority on psychopathy and creator of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, a tool widely used in making parole decisions) concluded that psychopaths are able to gain release from prison 2.5 times earlier than their undiagnosed counterparts because of their extraordinary ability to con and charm others. They also re-offend at higher rates.

Hare stresses the extreme difficulty even trained professionals have in seeing the truth underlying psychopathic manipulation. Despite his vast experience, he admits even he has been fooled. For this reason, parole board members, forensic psychologists, prison staff, and others involved in the criminal justice field should receive enhanced and ongoing training in psychopathy. While research shows convicted murderers who have served decades in prison have very low recidivism rates, it still cannot be in the best interests of society to release people like my brother who retain the same qualities of callousness and lack of empathy which enabled them to commit their crime in the first place.

All states should also pass legislation (similar to that on the books in Indiana) that make it a felony for a prisoner to perpetrate a fraud on a free person. Similarly, parole boards should create regulations holding prisoners accountable who take advantage of free people for their personal gain, even if such fraud only comes to light after their release. These measures will discourage people in prison from engaging in such conduct, which they are currently able to do with impunity.

However, we are never going to have a perfect parole system. Infrequently, someone will be released who once again causes harm. Over the past 30 years, though, we have gone from a retributive system, which has sentenced over 53,000 Americans to death by incarceration, to a culture that honors convicted murderers as heroes returning from the brutal war of prison while failing to acknowledge their ongoing moral responsibility for the harm they caused.

Surely, we can strive for balance. We can recognize that most, but not all, people in prison possess the capacity for redemption, and all are deserving of the chance to demonstrate this capacity. We can welcome people home from prison as returning citizens, and support them in building productive lives without glorifying them. We can also acknowledge we cannot end LWOP without including the voices of those who have been harmed, treating them with the respect and compassion they too deserve.

Susan Lawrence, M.D., Esq.– Humanparts.medium.com

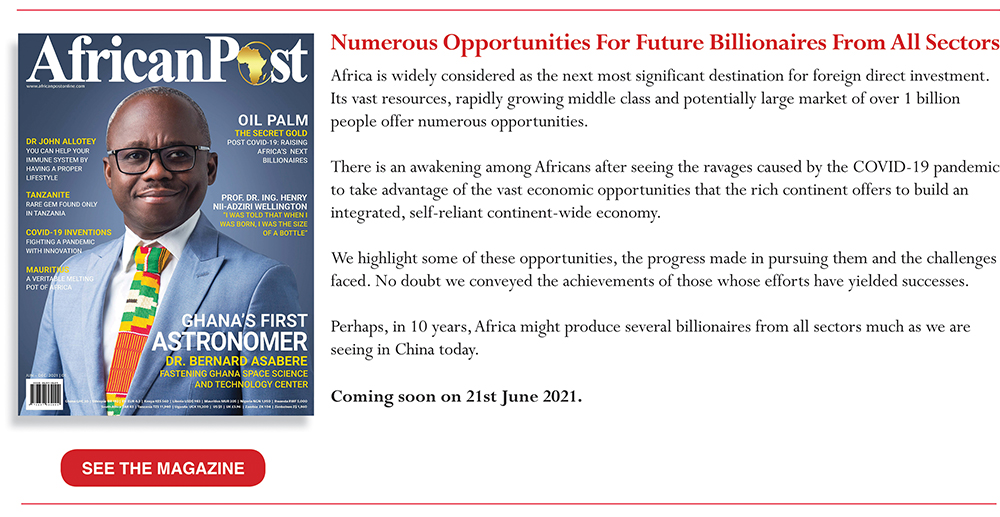

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.