Last year Rose Kalemba wrote a blog post explaining how hard it had been – when she was raped as a 14-year-old girl – to get a video of the attack removed from a popular porn website. Dozens of people then contacted her to say that they were facing the same problem today.

The nurse stopped at the doorway leading out of Rose’s hospital room and turned to face her.

“I’m sorry this happened to you,” she said, her voice shaking. “My daughter was raped too.”

Rose looked at the nurse. She couldn’t be older than 40, Rose thought, her daughter must be young, like me.

She thought back to the morning after the assault, to the conversations with the emotionless policeman and the clinical doctor. Everyone had used the phrase “alleged” when referring to the violent, hours-long overnight attack that Rose had described to them. With the exception of her father and grandmother, most of her relatives hadn’t believed her either.

With the nurse it was different.

“She believed me,” Rose says.

It was a small crack of hope – someone recognising and acknowledging what had happened to her. A wave of relief washed over her, which felt like it could be the start of her recovery.

But soon hundreds of thousands of people would see the rape for themselves and from those viewers she received no sympathy.

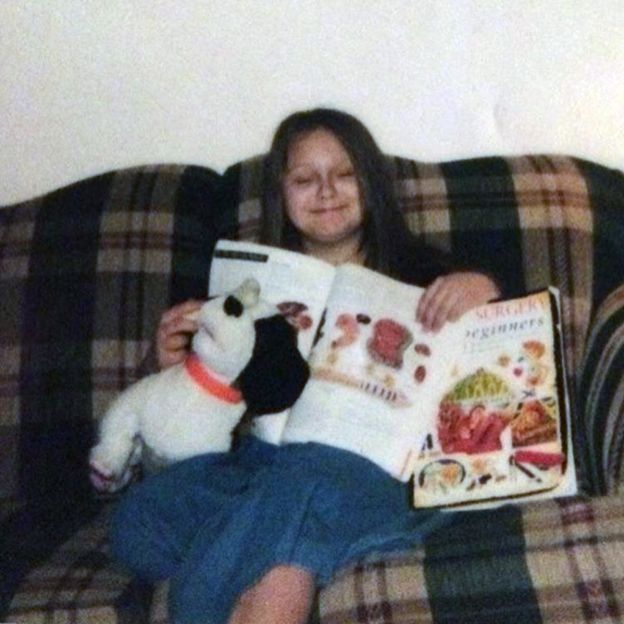

A decade later, Rose Kalemba brushes her thick thigh-length black hair at the bathroom mirror, twirling the ends with her fingers to form natural ringlets. This wouldn’t have been the case in the months after her attack – all the mirrors in her home had to be covered with blankets, as she couldn’t bear to catch her reflection.

She is now 25 and she has organised routines of self-care into her daily life.

Taking care of her hair is one. Combing it takes time and effort, it’s almost an act of meditation. She knows she has beautiful hair, people comment on it all the time. Every morning she also makes herself a cup of cacao, a pure, raw form of chocolate that she believes has healing qualities, and writes down her goals in a diary.

She deliberately puts them in the present tense.

“I’m an excellent driver,” is one goal. “I’m happily married to Robert,” is another. “I’m a great mother.”

Sitting down to talk, Rose pulls her hair over her shoulders – it covers most of her body, her own armour.

Growing up in a small town in Ohio, it wasn’t unusual for Rose to go for a walk alone before bedtime. It cleared her head, she enjoyed the fresh air and peace. So that evening in summer 2009 started like most for 14-year-old Rose.

But then a man appeared from the shadows. At knifepoint he forced her into a car. Sitting in the passenger seat was a second man, aged about 19 – she’d seen him around town. They drove her to a house on the other side of town and raped her over a period of 12 hours, while a third man filmed parts of the assault.

Rose was in shock – she could hardly breathe. She was badly beaten and stabbed on her left leg, her clothes bloody. She fell in and out of consciousness.

At some point, one of the men got out a laptop and showed Rose videos of attacks on other women. “I am of first nations ethnicity,” she says. “The attackers were white and the power structure was clear. Some of the victims were white but many were women of colour.”

Later, the men threatened to kill her. Forcing herself to collect her senses, Rose began to talk to them. If they released her, she wouldn’t reveal their identities, she said. Nothing would ever happen to them, no-one would know.

Taking her back in the car, men dumped her in a street about half an hour’s walk from her home.

Walking through the door, she caught sight of her reflection in the hall mirror. A gash in her head was oozing blood.

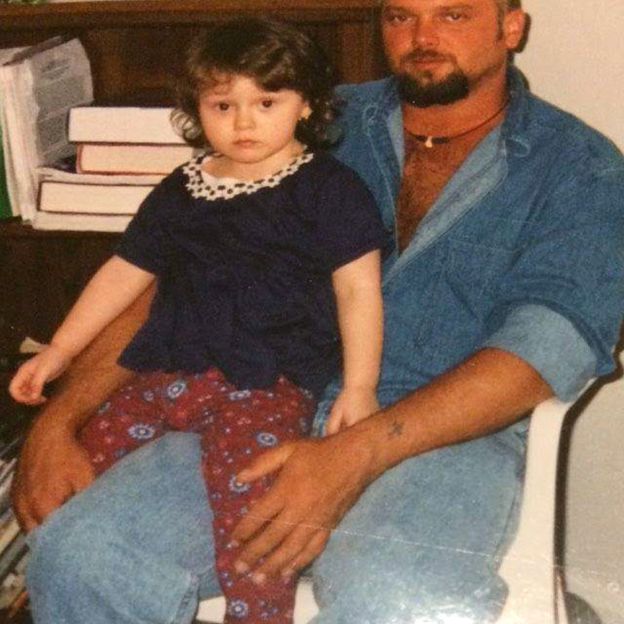

Her father, Ron, and some extended family were in the living room about to have lunch. Still bleeding from her stab wound, she explained what had happened to her.

“My dad called the police, he immediately comforted me, but the others said I had asked for it by walking out late at night,” Rose says.

At the hospital, Rose was greeted by a male doctor and male police officer.

“They both dealt with me in an extremely matter-of-fact manner,” she adds, “There was no kindness, no warmth.”

The male police officer asked her if this had started as consensual. Was it a night gone wild, he wondered.

Rose was stunned.

“Here I was beaten beyond recognition. Stabbed and bleeding…”

Rose told them no, it had not been consensual. And still reeling from what she had been through, she said she didn’t know who had attacked her. The police had no leads to go on.

When Rose was released the next day, she attempted suicide, unable to imagine how she could possibly live a normal life now. Her brother found her in time.

A few months later, Rose was browsing MySpace when she found several people from her school sharing a link. She was tagged. Clicking on it, Rose was directed to the pornography-sharing site, Pornhub. She felt a wave of nausea as she saw several videos of the attack on her.

“The titles of the videos were ‘teen crying and getting slapped around’, ‘teen getting destroyed’, ‘passed out teen’. One had over 400,000 views,” Rose recounts.

“The worst videos were the ones where I was passed out. Seeing myself being attacked where I wasn’t even conscious was the worst.”

She made an instant decision to not tell her family about the videos – most of them had not been supportive anyway. Telling them would achieve nothing.

Within days it was evident that most of her peers at school had seen the videos.

“I was bullied,” she says, “People would say that I asked for it. That I led men on. That I was a slut.”

Some boys said their parents had told them to stay away from her, in case she seduced them and then accused them of rape.

“People have an easier time blaming the victim,” she says.

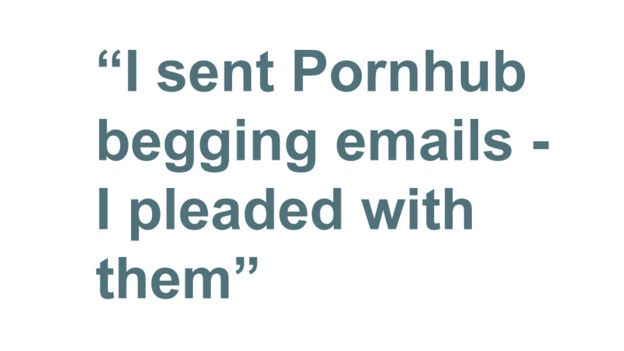

Rose says she emailed Pornhub several times over a period of six months in 2009 to ask for the videos to be taken down.

“I sent Pornhub begging emails. I pleaded with them. I wrote, ‘Please, I’m a minor, this was assault, please take it down.'”

She received no reply and the videos remained live.

“The year that followed I withdrew into myself. I disassociated,” she recalls, “I felt nothing. Numb. I kept to myself.”

She would wonder, with every stranger who made eye contact with her, if they had seen the videos.

“Had they got off to it? Had they gratified themselves to my rape?”

She couldn’t bear to look at herself. That’s why she covered the mirrors with blankets. She would brush her teeth and wash in the dark, thinking all the time about who could be watching the videos.

Then she had an idea.

She set up a new email address posing as a lawyer, and sent Pornhub an email threatening legal action.

“Within 48 hours the videos disappeared.”

Months later Rose began to receive counselling, finally revealing the identity of her attackers to the psychologist, who was duty bound to report them to the police. But she didn’t tell her family or the police about the videos.

The police collected victim impact statements from Rose and her family. The attackers’ lawyers argued that Rose had consented to sex, and the men were charged not with rape but “contributions towards the delinquency of a minor” – a misdemeanour – and received a suspended sentence.

Rose and her family did not have the energy, or the resources, to fight for a tougher sentence.

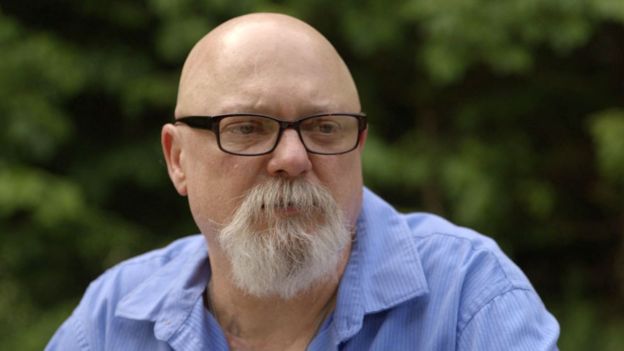

It’s clear that Ron Kalemba thinks a lot about what happened to his daughter all those years ago. What could he have done differently, if he’d known more, he wonders. His daughter changed after the assault. She went from being a straight-A student to missing classes, rarely handing in her homework.

We’re sitting in a park near his home that Ron visits often. He and Rose sometimes read from passages of the Bible from a picnic bench together. They don’t talk much about the past.

“It feels like the whole world let her down,” he says. “Her abuse, it was like it was a big joke to everyone. It changed her life completely, and people let her down every step of the way.”

Ron only heard about the Pornhub videos in 2019, when a blog that Rose shared about her abuse went viral on social media. He had no idea that his daughter’s rape had been seen by so many people, nor that people in her school had mocked her for it.

“I knew a girl in eighth grade when I was in school,” Ron recalls. “People would pick on her, and she would get beaten up. And none of us would say anything, we just watched it happen.”

“I ran into her years later and she thought that I was a bully too, because I had just stood by and watched it happen. In reality it had only been a couple of people who actually hurt her but she thought we were all against her because we watched it and said nothing. That’s what the silence felt like to her.”

Is this what he thinks happened to Rose?

“Yes but it was worse for her. She had a digital crowd of bullies too. Some silent and some abusive. Hers is a different world.”

Over the next few years Rose would often disappear into the digital world.

She threw herself into writing, expressing herself on blogs and social media, sometimes using aliases, sometimes her real name.

One day in 2019, as she was scrolling through her social media feed she saw a number of posts about Pornhub. People were praising it for donating to bee conservation charities, adding caption facilities for deaf viewers, donating to aid domestic violence charities and providing $25,000 scholarships for women who want to enter the tech industry.

According to Pornhub, there were 42 billion visits to its website in 2019 – an increase of 8.5 billion from the year before, with a daily average of around 115 million. And 1,200 searches per second.

“It’s impossible to miss Pornhub if you use social media,” says Rose. “They’ve done a great job at positioning themselves as a ‘woke’ mission, almost transcending porn, but videos titled like mine are still on the site. There’s no way of knowing if there are rapes on there and the victims don’t know it.”

In the viral blog post, Rose shared a detailed account of her rape, and called out Pornhub for turning a blind eye until she pretended to be a lawyer. Dozens of women and some men responded to her post, saying that videos showing them being sexually abused had also appeared on the site.

In a statement to the BBC, Pornhub said: “These horrific allegations date back to 2009, several years prior to Pornhub being acquired by its current owners, so we do not have information on how it was handled at that time. Since the change in ownership, Pornhub has continuously put in place the industry’s most stringent safeguards and policies when it comes to combating unauthorised and illegal content, as part of our commitment to combating child sex abuse material. The company employs Vobile, a state-of-the-art third party fingerprinting software, which scans any new uploads for potential matches to unauthorised material and makes sure the original video doesn’t go back up on the platform.”

When asked why videos with titles similar to those uploaded featuring Rose’s rape, such as “teen abused while sleeping”, “drunk teen abuse sleeping” and “extreme teen abuse” are still active on Pornhub, the company said: “We allow all forms of sexual expression that follow our Terms of Use, and while some people may find these fantasies inappropriate, they do appeal to many people around the world and are protected by various freedom of speech laws.”

Pornhub introduced a flagging tab for inappropriate content in 2015, but stories about videos of abuse on the website continue to surface.

In October last year a 30-year-old Florida man, Christopher Johnson, faced charges for sexually abusing a 15-year-old. Videos of the attack had been posted on Pornhub.

In a statement to the BBC regarding this case, Pornhub said its policy is to “remove unauthorised content as soon as we are made aware of it, which is exactly what we did in this case”.

In 2019 Pornhub also removed a channel called Girls Do Porn, when 22 women sued it for forcing them to take part in videos, and the channel’s owners were charged with sex trafficking.

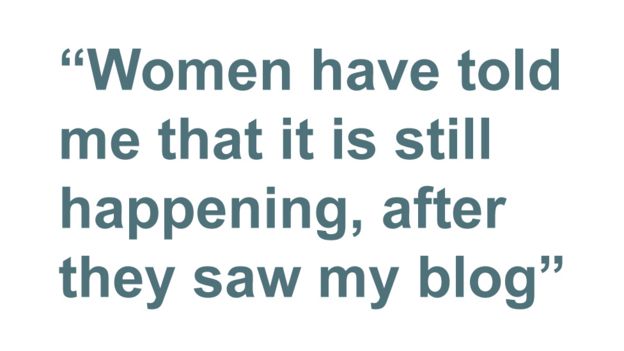

“People may say that what happened to me a decade ago isn’t a reality of today, but that is simply not the case,” says Rose.

“Women have told me that it is still happening, after they saw my blog. And these are Western women with access to social media.

“I don’t doubt that videos in other parts of the world, in places we know porn is consumed in large bulks like the Middle East and Asia are places where the victim might not even be aware that their abuse is being shared.”

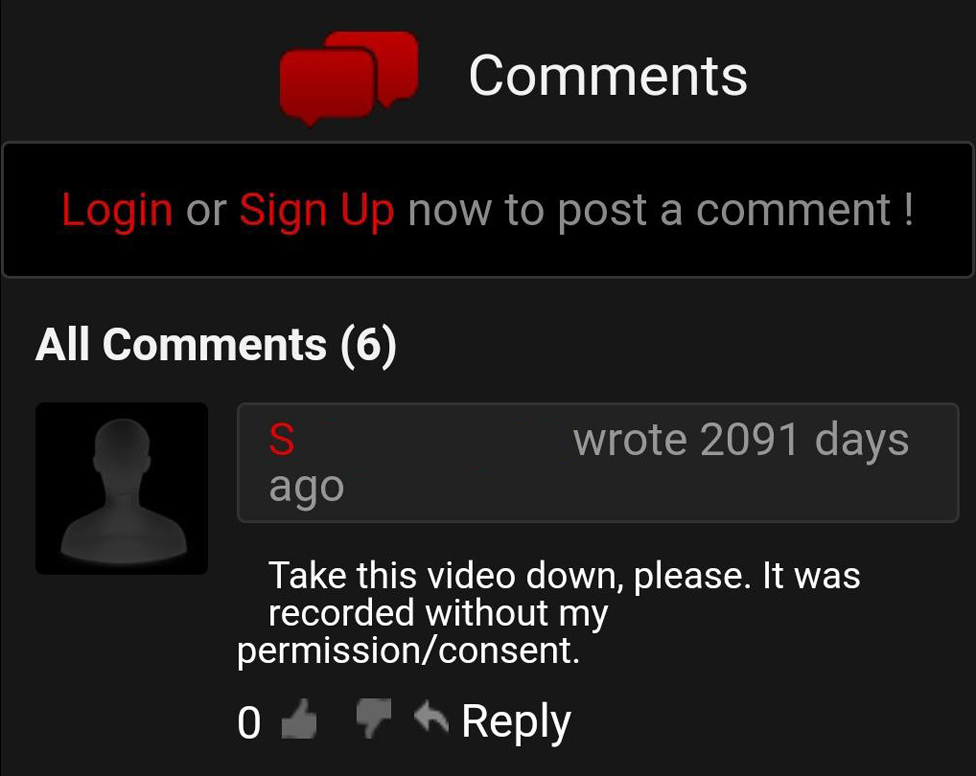

The BBC also spoke to one woman who emailed Rose. A video showing her being abused remained for years on a smaller site, even though she sent several emails to the company, and left a post in the comments section under the video. The woman, from California, says that the video has also been downloaded and shared on other porn sites. Lawyers for the website told the BBC that their clients had “no knowledge of any such situation”. The BBC then provided a link to the video, as well as screenshots of comments by the woman requesting for it to be removed. It was finally removed in the following days.

“What happened to Rose in 2009 is still happening today on several free streaming porn sites – and not just Pornhub,” says Kate Isaacs from Not Your Porn, a group that investigates porn sites.

“There’s nothing we can do about rogue, smaller porn sites set up by individuals but large commercial sites like Pornhub need to be held accountable and they are not right now. No laws apply to them.”

So-called revenge pornography, which is a type of image-based sexual abuse, has been a criminal offence in England and Wales since 2015. The law defines it as “the sharing of private, sexual materials, either photos or videos, of another person, without their consent and with the purpose of causing embarrassment or distress”. It is punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment. However platforms that share this content have not been held accountable so far.

“Porn sites are aware that there is disturbing and non-consensual content on their platforms,” says Isaacs. “They know that there is no way we can differentiate fantasy role-play acting, or faked production scenarios, or real abuse.”

She set up Not Your Porn when a sex video featuring a friend of hers (who was under 16 at the time) was uploaded on to Pornhub. Kate says more than 50 women in the UK have come to her in the past six months to say that sexual videos have been posted without their consent on pornography sites. Thirty of them were uploaded to Pornhub.

She also points out that Pornhub and other websites enable viewers to download videos on to their own computer – so even if the video is taken down from one website it’s easy for any of these users to share it or upload it again to another.

Not Your Porn are campaigning for laws in that UK that would make the sharing of non-consensual pornographic videos a criminal offence.

Rose has hope for the future. In her early 20s she met her boyfriend, Robert, who she says has helped her discuss and come to terms with her abuse. She hopes they’ll get married and have a daughter. And her dog Bella, a pitbull is a source of strength.

“I’ve grown up around pitbulls. They may have a reputation of being aggressive but they’re so sweet,” she says. “They’re aggressive only if abused by humans,” she adds pointedly.

“In many ways, I have a life sentence,” Rose say. “Even now I could be at the grocery store and I wonder if a stranger has seen my video.”

But she no longer wants to be silent, she says.

“The most powerful weapon of a rapist is our silence.”

BBC

Putting a spotlight on business, inventions, leadership, influencers, women, technology, and lifestyle. We inspire, educate, celebrate success and reward resilience.